Teflon and Resistance: disordered eating, indigestible truth and healing

A conversation between Jasleen Kaur (Be Like Teflon) and Raju Rage (Recipes For Resistance)

Chapter 1: Teflon and Resistance

JASLEEN: I want to hear so much more about like…how much this has been in your body for! You’ve been working on this for maybe three, four years?!

RAJU: Yeah. Yeah for sure…so…I can’t really remember exactly where it began….but it was in the British Library archives…where I was trying to search South Asian migration into the UK and empire…and those connections. A lot of what was coming up was army and military. I was interested in that but also looking for more female narratives and I was like….there’s not much there. I then made another work around that, in terms of the lack of S Asians Women’s narratives in the colonial archives.

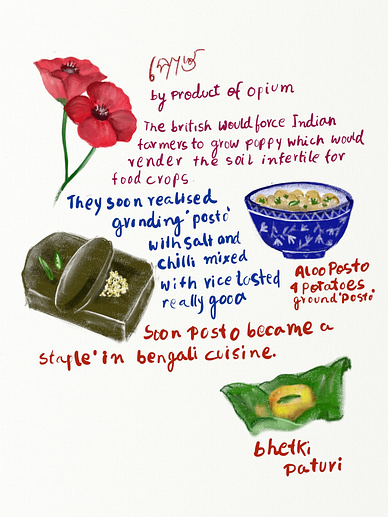

What I did find though…and quite interesting….looking at British Empire and South Asians as part of Empire, were things around food. There was a conspiracy in the British Army that S Asian officers were passing messages through chapatis and I was like – WOW – that’s a really interesting form of resistance…even if it was not true, this panic of South Asians soldiers passing messages in the chapatis and infiltrating the British Army. I was like – that’s just ingenious….just…even as a … like…

JASLEEN: A visual?

RAJU: Yeah! I was just really interested in that as an example of resistance and for the little ways that we create resistance…you know? I think it just opened up my eyes to this idea of what resistance can be. So, I just decided to pursue that lead and found other things around British Empire providing certain cultural diets towards different officers, Muslims and the Hindus who didn’t want to eat beef or pork…and I thought…this is super complex. I was finding these really weird things, that I thought were fascinating and I thought – this is much more interesting than the stuff I was trying to find in the first place. I was just thinking through when we first – SORRY THIS SO LONG WINDED – migrated here in 82′. We didn’t really have much family here, but my father’s friends were working in biscuit factories…McVities….and I remember going round to their houses and having biscuits as an exotic treat. I just thought, yeah…this memory is so funny because I found some similar material from the S Asian evictions from Uganda around diet, when people first came here and were in these refugee camps eating this unfamiliar palette of cereal and beans on toast and putting their own spices and flavours in, or they got incorporated in later when tastes for them had formed.

These kinds of narratives really started to speak to me about adaptability and how we survive. I was always interested in food – because of my background in baking and cheffing so…I just thought… yeah, actually THESE narratives and my food practice is what I need to focus on, instead of endlessly looking through the British library…getting so drained, being told off constantly when I was there …. it was just a really hostile place, and a hostile mode of research and investigation. This just felt comforting, and that’s what I liked about your publication as well…there’s these heavy narratives, but there’s something comforting about reading them, in this kind of environment…where these shared conversations around food are happening…This isn’t theorised and it shouldn’t be, this is the way that resistance manifest/ed in lived experience. But it’s also not valued or recognised as such, when I have conversations with family it’s just not seen as…’oh yeah, our recipes adapted when we migrated to different places as resistance’, and it’s not really spoken about in that way. I just thought well how are these things being spoken about and how do I want to frame them. For me – being queer and trans – and having difficulty with my own family around my identity, but me also not knowing much about my grandparents and our migration, and our histories…cultural history, I questioned, ‘how do I want to have these encompassing conversations?’

I had found a good way to have difficult conversations with my mother was through food, we’d meet and we’d cook together…and then I could ask questions and find out information about heritage. That all came together at the same time…and so this was all like marinating and I wasn’t really sure how to put it out there and in what form…and then I read this quote by Almah LaVon about how we symbolically build resilience and resistance through adaptogens as recipes for resistance…so everything was just kind of coming together in this way, so I thought…I really like this term, ‘recipes for resistance’ as it opens things up. So I thought….let’s do something with that.

I started gathering material and started playing with it, putting things together. I watched Richard Fung’s ”Dal Puri Diaspora”…which is an amazing film about the migration of the puri from South Asia to Trinidad and the Caribbean, but also it isn’t the straightforward linear narrative of migration…of fusion food…it’s kind of saying – yes, things migrated, but also that things became their own and actually there is no origin, there is no authentic…it’s just…things just coincided and exist together simultaneously. It doesn’t belong to one or the other…and to both. I was pulling all of these threads together and wondering what I focus on? I started to put together a compilation that was about the roti…and then that was taking time to come together and I felt like, there’s going to be so many gaps and missing parts and I didn’t know how to reconcile that in that way.

JASLEEN: You mean like historically factual stuff?

RAJU: There’s so much with the roti that I wouldn’t necessarily be able to cover you know? There’s roti in South Asian culture, in Caribbean culture.. there’s just so much. Meanwhile Ort Gallery contacted me about doing an exhibition,….I was thinking about Birmingham…and about S Asian migrant communities there and about food. And it just suddenly dawned on me.

JASLEEN: Hmmm

RAJU: It can be an exhibition even though it had started out as much more of a publication, I wanted material to speak to each other and be in conversation with each other. So, that’s how it came to be.

I wanted to connect people’s work where there’s these running threads and conversations. I felt much happier about doing it in that way, although it became so ambitious with the budget that I actually had but I/we made it work and generated more funding for it through the sale of the publication so it did work out for it to also exist as a publication in its own right and it meant it reached further than an exhibition also.

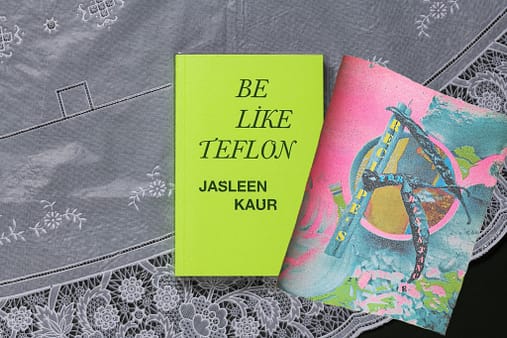

JASLEEN: It’s so great to hear. Because for me, when I was reading through it, I could feel the differences between it and Be Like Teflon. It felt really expansive and in part educational. Recipes For Resistance is really a political piece of work. You weave in so much creating this new landscape in which to implant these conversations in, and it points to a future as well — which I love.

I want to ask you about that in terms of your trans identity and queerness and the possibility of transformation and breaking out of these patriarchal gender binaries…and where Teflon really stays in that place. I think when you asked that question in your email about an uncomfortability with Teflon, that really felt like a gift actually…to pose that question to me.

RAJU:– Yeah, I wasn’t trying to be critical, that’s what it brought out from me, which was important…yeah!

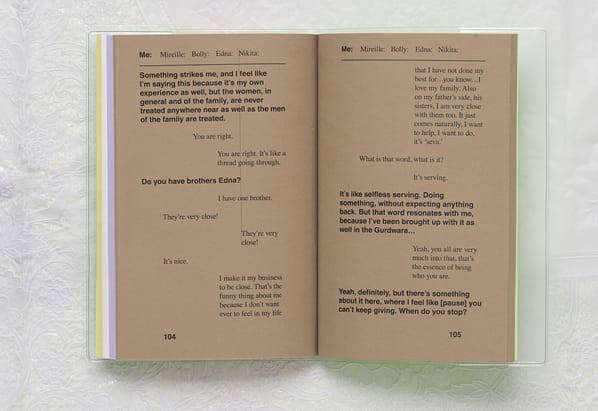

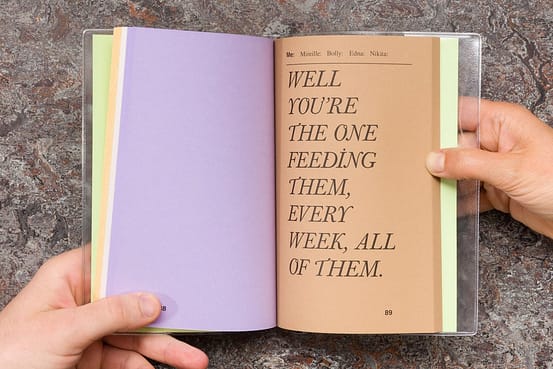

JASLEEN: In a way, it gave me a new lens to look at Teflon. It made me look at it’s restrictive qualities of womanhood and of centering womanhood, but also the process of this book really coming from a place of like *sigh* really having to sit with familial traumas that are rooted in patriarchy — rooted in abuses that are enacted from men onto women. I really feel that this is a process…like if I was to turn to the subject now – three years on – it would be something else. It’s really nerve racking to read it again and to see the rawness and unedited nature of my voice in it and the unedited nature of having these conversations, but I also wanted to trust or honour that because it’s not an academic text or heritage project. It’s not representative of all ”South Asian-ness”. This was commissioned for a white institution – Glasgow Women’s Library – amazing as they are, I really wanted to hold back in what I/we put out into the world and care for those intimacies shared in the book. So to decide, for example, that four short conversations was enough!

But yeah, there’s something about identifying as ‘woman’ and the restrictiveness of that in the book. It doesn’t look forward…it goes back into history…back into households that I grew up in….back into gender roles that perpetuate these cycles of harm.

RAJU: I mean I really love your publication. I find it amazing on many levels and I agree with you that it is this going back…but I feel ‘super important to do that excavating and the uncomfortability that it brought out from me is also this…this fear to go back to that place, with that person that I left for a reason because of patriarchal violence. I have guilt because I know I left that space.. it’s not like I completely left patriarchy behind…but there was some refusal and ability to leave that situation where – it’s very clear that…it’s not necessarily possible for many women specifically…so it was that uncomfortability of this guilt that I carry around…but at the same time…this not being able to fit it, because I do fit into these narratives, but I also don’t quite fit into these narratives…and then it’s kind of like, where are these other spaces for me to discuss the kind of patriarchal violence I faced as a trans person?…and the impact that it had in the journey I took and the decisions I made.

I questioned my place as a reader of it, but I think when we had that event and panel at Glasgow that you invited me to share work at, I suddenly thought …. should I be here? Should I be sharing my experience….is it appropriate for me or not? I left with that question,….whether it is important for it to remain in that place (of women’s experience) and not be taken out of that, because I think there is still so much to be uncovered and unpacked around that…and I think for the same reason that women’s spaces should be respected. There is a need for a women’s only space, to kind of delve into these issues and yet there is a shared experience of sorts…so I think this is the same conversation for me – do I belong in this? Or, how can I belong in this without interfering but also fitting in…because I don’t identify…I’m not a MAN and I don’t feel male in this sense….I still have that side of me that’s ‘feminine’ or whatever…and have experiences of being assigned female and the oppression that comes with that socialisation, but i’m also not female. It’s complicated

JASLEEN: Hmmmm

RAJU: I appreciate the heaviness that it brings and maybe I’m being clumsy with my words…but I felt like they were difficult conversations that were had….that I just really respected. I also respected that you put that into an art institution and challenged it by using these narratives and that it wasn’t this native informant kind of way. I was really interested in how people would receive it because I received it in a very specific way.

I just feel like it’s a great publication, but there’s a wider conversation that can continue around the responses to it. Which I think I would really love to have. I mean it’s interesting what you’re saying around perpetuation because I think…yeah inevitably some of that does happen but also…some more important work is done at the same time.

JASLEEN: Hmmmm…

RAJU: It’s not binary in that way…it’s like these things exist in complicated ways…just like Recipes For Resistance, there are gaps and missing pieces. And I thought, I’m probably going to be criticised because of ‘representation’ (and its burden) and ‘inclusion’ but then I was like — I can have ongoing conversations with people and get these creative responses to fill those missing parts…and you know…more can be generated from this…

JASLEEN: Yeah…

RAJU: It’s not just beautiful as it is as a material object, it’s not just a material object to be kept, it’s something outside of that as well.

JASLEEN: Yeah..yeah… they’ve taken the form of books …they have pages and they have printed text on them…but I don’t see them as books in that sense. They’re speaking right? They are voice!

RAJU: Yeah…true

JASLEEN: I really feel what you’re saying about making a space for Recipes For Resistance to exist — you’re creating a world basically…it’s like world building isn’t it? This is the fullness in which you want people to understand, or you want these stories and narratives to exist within…you need to provide the landscape in a way for them to be held correctly.

RAJU: I wanted to create a landscape you know…in the sense where and in which I see relationships and networks but I don’t necessarily experience…the conversations happening…you know?

JASLEEN: Hmmm

RAJU:The complexities and the nuances of all of these conversations and how they’re connected, I want to see more of that happening…so I felt like I needed to allow some sort of platform for that to happen. Not to say that I’m the only one doing that, so many other people are out there doing that…so I was like…yeah…I want to connect to you and to each other as well.

How can we have this broader conversation with each other. But also not to limit it to the art world. These conversations are also happening outside of the art world. I feel like people have been doing that for a while. For example, who’s that politician from Uganda who wrote a recipe book…

JASLEEN: Is it a memoir?

RAJU: Yeah…it’s a memoir and it’s a cookbook, but it’s just so assimilationist

JASLEEN: Yeah…yeah…I remember…probably like 10 years ago it was Radio 4’s ‘Book Of The Week’…

RAJU: The Settler’s CookBook by Yasmin Alibhai Brown.

JASLEEN: That one! Yep!

RAJU: Yeah there’s things I liked about it, the format and recipes, but I just didn’t like the narratives…I just thought it was so non critical discussing South Asian positionality in Africa. I wanted to produce something that could go deeper into the wider politics of food.

JASLEEN: When I was invited to create something for the Glasgow women’s library, I had a brief period of time in their archive and these working class recipe books stood out to me. And on a personal level, returning back to Glasgow…I wish my mum knew about these spaces. I was thinking about how she, as a woman, really doesn’t fit into the South Asian community because of how women uphold patriarchy in those communities. There’s an awful lot of showing face, and so she kind of opts out. I wish she had a community in which she could…I don’t know…just get to speak more, because she’s got a lot to say.

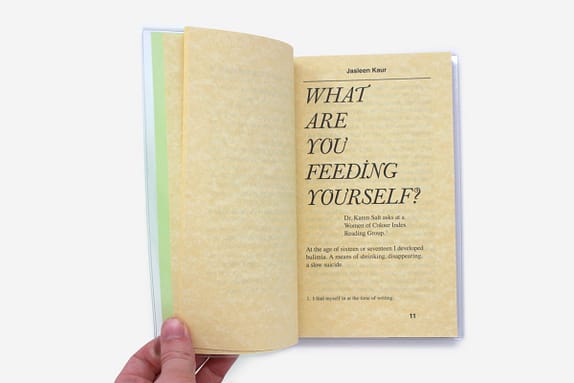

Chapter 2: Disordered Eating and indigestible truth

JASLEEN: I think that was the impetus. The thing that was going on for me at the time was…um….uh…confronting a lot of personal trauma…and…really wanting to speak! Right?! And really struggling to write because when I decided that this was going to take the form of a book, and a recipe book, which didn’t exoticize, in all it’s breadth, that did not flatten…I couldn’t start writing. It starts with disorder right? It starts with disordered eating, it doesn’t start with beautiful, nourishing food. It starts with ‘I can’t eat!’.

It took me a long time and I paused the project thinking ‘’I don’t think I can do it’, because I didn’t know how to write personally — testimony was not going to emancipate me — and who was I writing for? I wanted to ask about this as well. How do you do that? And also about how your Pure Realm Instagram page functions as an online space for you.

RAJU: I just realised a parallel between the two books, because they both…start on disordered eating, or indigestible truth or whatever…and I hadn’t noticed that before. But I made that choice because I thought Zarina Muhammad’s ‘Eat The Rich’, just really provided a good foundation and context to the politics of what I wanted to explore. But yeah, I like that parallel that’s really interesting. I really appreciated you sharing that and feel it’s important to acknowledge it when we speak about food, recipes and politics.

I’ve struggled with past trauma and not having a voice or not feeling like I could speak or where I can have these conversations, who to have them with, disconnection with South Asian culture and community because I think I rejected it as I was simultaneously rejected. So, it was very tainted for me. I just had always internalised my trauma- you self-blame and you think you were a part of the problem, so you don’t speak up about it. And then, I realised at some point that I wanted to center a healing perspective – of wanting to heal….wanting to process even…wanting to unpack what’s going on.

I also don’t want to fall into victim trauma narratives at the same time. So, I wanted to actually create something that is real and honest and pure. Not because I believe in ideas of purity in caste sense…it’s just pure in terms of uncensored…everything’s there…in all its nuance…it’s messy…it’s just bringing it authentically in that sense.

JASLEEN: Yeah…

RAJU: I guess I’m unapologetic about it and I just feel like I want to see more of that happening around me.where we’re not afraid to speak out truths. But I also want to have some control over how that’s then consumed. I am weary of where and how I would do that. You know of trauma-porn. I’m sometimes wondering in my sharing…am I over sharing? But then I remember Adam Farah who said once about how oversharing is an antidote to neoliberalism…let’s just over-share our lived experience, especially the stuff people don’t want to necessarily hear or beyond what’s palatable. I think it’s about questioning how mainstream institutions want narratives that they want to hear from us and how they can capitalise on it? I was considering what we can actually put out there…that’s real…that maybe people find uncomfortable and difficult to take on board. but is really important. Again that’s why I like your book…it does that…you know?! It’s not trying to sugar coat it or whatever for that institution who desires that.

JASLEEN: You mentioned over email about the theme of digestion and indigestion in Teflon… and indigestion was really on point. There was something around like…in the process of putting Teflon together…and I wonder if this has come up for you as well? Everything we’ve been chatting about really…wanting to speak your truth but also not wanting to provide content.

In my draft I’ve got a whole glossary of non-english words that were spoken in conversations, sometimes whole conversations were translated into english. So, there was that process of translation, but then I made the decision to take out all the italicised words and bin the glossary…because that is the colonial format, that you’ll see in archived books from British Raj for example. So the decision to refuse explaining and refuse consumption — even in a small way — felt important.

RAJU: I had a similar experience with one of the works in the exhibition called ‘Eat While You Feed’.

In one part we were having a really amazing conversation where aunty was talking about patriarchy, about what’s expected…different roles…and how she stepped out of that…and how she does things differently…she has a disability…she takes care of herself….some quite intimate stuff. Now we’re going through the process of editing that and they really love it – but she’s not quite sure…you know the parts with her disability because she’s been so stigmatised…for having a disability within South Asian culture…especially around Hindu Cultural concepts of karma. So she wanted to be careful. I had to have a conversation about the importance of having these narratives…and having these kind of role models in a sense…but then I was like ‘you don’t need to be a role model’ at the same time.

So, I’m also asking myself am I doing the right thing, ethically?Because I feel I would like to see this in the world because this is still ongoing, in terms of like the violence and harm that happens within our communities, and it’s important to know that there are other ways….and it’s not just the younger generations who are changing the landscape of things….but those older generations as well.

JASLEEN: Yeah really similar from what you’re saying really. For Amanroop who talks about her mum’s death in a really detailed way. In our conversation whilst making Aloo Parathay…she goes on a really…that thing about trauma really…you can ignore it for years, but when you do come back to it…you know it intimately…moment by moment…you know the smell of the room or the tone of light…

She could go into the detail of it and for her it became like a really cathartic process. We did tweak quite a bit to the point where Amanroop felt like it was safe to put out there.

The conversation with my mum…for me…is quite symbolic in how stunted it is…and how little can be said…and how uncomfortable having conversation is…and that’s why I choose to put it in there. Our conversation is quite rigid — it goes nowhere. Teflon is so much about the silence, honouring the beginning of voicing and what can’t be said yet.

But yeah, like you say, there is a void and a lack which I speak about in the intro of these authentic narratives, of these painful narratives…uhhh narratives doesn’t feel like the right word…There’s something that you were chatting about…about eating while you feed…

RAJU: So, ‘eat while you feed’ is the idea that you feed yourself…while you’re feeding others. So, you care for yourself as you care for others..but, what I’ve noticed…and this came up with aunty in the film that we made where she thought it undermines that satisfaction of you feeding other people, if you eat while you feed.

JASLEEN: Oh wowwww….

RAJU: So, she doesn’t do that…she would eat afterwards….that’s her rule. I noticed that my mother did this, she would always…to the point where it was really creepy…she would watch us eat! Then she would eat after us. I’ve noticed this happens a bit in the South Asian culture that I’ve been exposed to…women (the main carers) do this thing where they eat afterwards…or they only eat with other women. I just thought it’s super interesting because for me as a self-care thing I like the idea/concept, maybe it’s more metaphorical…but yeah we take care of ourselves as we would take care of others. I like the idea that we also nourish ourselves, but I also wondered whether….there was a part in reading your book where it discusses self-care…it’s also about taking care of yourself, by separating yourself…that is also an act of care, right? Maybe you don’t want to be necessarily eating with everyone, maybe you take your time and your space. And I think that’s also what my mother did – she worked hard all day as a single mother and then she took her time and her space and watched her Indian soaps (VERY LOUDLY) on the TV.

JASLEEN: I can totally second everything that you’ve observed around, like, whatever aunty was saying right? Around this desire…to be a feeder? Which is what Amanprit Sandhu writes about in her parallel text ‘The Feeder and Feeding’. You’re taking me back into the kitchen right now. My mum would have the last roti on the tawa, she’d eat last and she would leave it there because she liked it crispy.

RAJU: That’s nice!

JASLEEN: And as she turned vegan, and therefore her diet became different to others in the house, she’d make the last few rotis without butter. So, there were some practicalities around it too, but absolutely, it was rooted in duty, and in whose labour was more valued right? Mum could have been working all day, but dad would come back from the shop and he would be fed first, and probably complain about what was made? But you asking that question also made me realise what it is that I do…in my home.

RAJU: Oh yeah…what do you do?

JASLEEN: Well…I do like what my mum does right? I cook the dinner….

RAJU: LAUGHS…Yeah… I do too!!! Yes…yes!!

JASLEEN: I want to feed Rai the amazing things I grew up on. I really feel like I carry a lot of that feeder mentality and that I should be weary of that. And…that I think that as Rai grows I’ll be conscious to involve him in kitchen life. I mean his mixed heritage-ness also makes things different for him too.

What was that saying, something around eating while you…

RAJU: Eat while you feed…yeah…

JASLEEN: Yeah..this idea of purity and food being SOOCHA, is that a word that you’re familiar with?

RAJU: Hmmmm….mmmm

JASLEEN: Where ideas of cleanliness and purity enters into food and mainstream ideas of Sikhi. I’ve been trying to trace back and understand how this mainstream narrative of Sikhi came to be? And what are the factors in that? I’ve been thinking about how caste played into like…ideas of like…being a Good Sikh or a Bad Sikh.

Meat and Caste are a really new territory for me, but what I deeply love about Recipes For Resistance is those narratives are woven throughout.

RAJU: I mean… I’ve always been interested in this whole conversation around vegetarianism and the practises of not eating meat and how that’s communicated. I’m just kind of coming to terms of yeah how caste played out and what that meant for us. We left my (Hindu) father when I was 7…we didn’t know any of his family, so I didn’t have that direct familial socialisation as far as I know outrightly about caste and from what I know caste is not really inscribed – it’s ascribed right? So, it’s about socialisation. But I think it still played out. Ive been trying to pick that apart.

My father would always complain about my mother cooked! There was always stuff around food that was so violent so it’s surprising that I didn’t actually grow up with any eating disorders myself. And I’m kind of always surprised that I’ve taken to food in this way (being a chef and baker). But I think I also took to food because…it created this agency….I can cook, I can cook for myself and I often had to as a child in a single parent household also but also being surrounded by community kitchens.

JASLEEN: Yeah…you mentioned Langar and Seva as well.

RAJU: I mean, It’s something that I’ve been really interested in doing…in terms of feeding those who can’t feed themselves or you know taking care of people through feeding…being a FEEDER…all of these things are part of my identity. I just kind of do it and then I realise this is part of Seva that I grew up with as Sikhi. I know from your work that you bring that in (for example in 5K’s carpets).

JASLEEN: I feel like personally, I’m in a real space of unlearning to relearn with Sikhi. There’s just so much beauty in the ideas of where Langar comes from — this idea of feeding everybody the same meal, on an equal level. In the context of what we’ve just been speaking about around caste, that’s a really powerful act. What you were saying about feeling a real affinity with that, it’s just something deeply socialist and beautiful.

You made me think about the performativity of Langar though. Like, what is it doing in our current context. I have a problem with mainstream Sikh identity and spaces of worship today. They’re deeply conservative and so what is Langar doing today, that it was meant to do 550 years ago right?

There are now these Langar vans that go out into communities of need and I have a real push and pull with that…it’s inherently a good thing to do…but it’s also like a lot of…

RAJU:…saviourism?

JASLEEN: Yes! And posturing as a good citizen and where that plays into being a brown citizen and…a lot of the time that’s the shit that makes the news right? Like there’s the BBC doc on whatever right? And I just feel like this isn’t what Sikhi was. It’s now really right wing actually.

RAJU: I agree with you. I’ve been to Gurdwara’s where people just interrogate who you are, who your family – who your parents are, what your surname is, what job you do…you know…these kinds of things…and I’m just I just came here to pray and eat langar? You know?! Why do you need to know who I am and where I’m from, to place value on my body or whatever.

JASLEEN: Yeah…yeah…

RAJU: So, I have these negative experiences…but I’ve also had amazing experiences of sharing food in Sikhi community with an incredible generosity and giving spirit.

Chapter 3:Healing

Raju: I wanted to come back to the publications and the titles because…I feel like they both have very powerful titles. I think what I’ve noticed from me putting it out there is people really connect to the title but I actually haven’t had a huge lot of feedback for Recipes For Resistance…maybe just because of what’s happening at this time of a pandemic.. I think it also takes time to digest. I’m pleased that the publication has migrated so far and wide and seems to be very popular. I would just like to know what people think! I also wonder how brave we can be about putting out these narratives…or I was thinking about that in terms of how readable is it going to be…are people just going to turn off because the contents going to be too much or too heavy and indigestible…or whatever

JASLEEN: In all honesty, I don’t really feel like I had a lot of feedback. I’ve been quite shy with this work.

When Teflon was launched in April 2019, I was coming up to giving birth and so…actually I think I switched off from it. I wasn’t looking to do interviews. I think it helped that Zarina wrote a review on it recently because I think it signalled a lot of new people. I noticed the book was falling into different hands, so I was really grateful for that.

So in all honesty, Zarina’s review and the conversations with Amanpreet Sandhu…and now my conversation with you, have been the most valuable conversations around it. I think I do a lot of processing in hindsight. I work with a lot of gut feeling and in turn gives me a huge amount of self doubt. Especially when I’m working with such embodied stuff.

RAJU: That’s interesting to hear. It also begs the question of why do we put out these publications. It’s already reached so many different contexts , so then I was like OKAY…So people are really interested in this and a lot of people bought it but what are people getting from it or what is it doing for people?!

BUT also there’s this question of audience because…SO YEAH…maybe it’s just about me having specific conversations with specific audiences.

JASLEEN: Yeah…yeah… I mean personally there’s one bit that really — I MEAN there’s so many bits — but, there’s this bit in this Queer Masala piece about bastardising and creating new food lineages and histories in these new lands. I love how you weave in narratives of land. I guess it’s resistance, but it’s also a reclamation. It’s also really speaking to me at the moment because I’m in parks a lot and I’m watching what Rai pick dandelions and daisies to eat! And of course you speak about how foraging has white connotations and the re-ownership of that is beautiful, especially in Hackney, Bethnal Green areas that are incredibly gentrified.

RAJU:Yeah, also around…lineages and ancestral knowledges…but also when we are disconnected from that – we also have to find our own way and we do bastardise things… we do things differently and that being torn between lands or belonging…or how we’re made to feel like we don’t belong…and we don’t connect to the land so…yeah…I think that conversation is so deep that it could maybe be a whole other round table or something.

JASLEEN: That’s the other thing right? That we’re working with edited material to create something that’s legible. Even with this conversation, if we decide to put it out into the world it’s going to be, you know, a version of something.The other thing that it speaks to is the moment you realise you’re gluten intolerant and you start to make spelt roti and you mention that that is what our ancestors actually cooked back in Punjab. And I was thinking about the Green Revolution and how that skews our sense of food history and identity— this idea of fitting into this perfect Punjabi identity doesn’t exist. Like, geographical Punjab is bordered by so many places — something created Punjab…right? It’s constantly in flux…

RAJU: Yes exactly…

JASLEEN: … What you’re talking about in Queer Masala’s piece around…shifting lands and movement…and so much of what we’ve been talking about around Sikhi as well. What impacts that…and puts it on a trajectory…and how to reject that…

RAJU: I have no idea…what I can claim…and I think this sense of being in this land as well…being told who you are…but also what you can and can’t access in relation to land…I’ve been trying to go to the countryside and …you know…visit the rest of the UK and that’s just been like….I’M 42..this is CRAZY, I’ve grown up here most of my life, and.it’s only something recent that I’ve been able to say…NO….I want to feel some sort of connection to the land here despite the colonialism I carry….ummm….

In terms of the foraging…again I just felt like…oh I don’t have this knowledge…or…it’s not mine to claim so it’s not something that I can do…but…recently…and through Rajiv and growing things in my garden…have embraced that more…and learning more about what’s growing…the brambles, the berries…you know. I actually remember when we first moved here to the UK we had blackberries in our garden, and we used to make jam when I was little. So, it kind of takes me back to first coming to this country in the early 80’s…and being racially abused, but then…HAVING THIS BLACKBERRY JAM!! And again – these stories – like the Ugandan exile stories of this really strange sense of being removed from a place but then…having this NOT NECESSARILY comfort food but food that’s new to you, that you’re embracing in this curious way but also adding to so – for me – it’s the constant contradiction and addition-ing….umm…that exists yeahhh..

JASLEEN: I wondered whether we could maybe think about healing and food? You mentioned earlier about coming into art as a necessary process of healing…and the healing properties of art. I’m wondering what it means for you in terms of the things you’ve been growing in your garden? I feel really inspired by seeing all the things you grow…chickpeas, ajwain…at some point when I have space, I wonder what I will grow and how we tap into the ancestral via that process…having my fingers in mud…and nurturing something that in turn nurtures us.

How do you approach food and healing?

RAJU: I mean its cliche but I really love the process of cooking…because it’s a very mindful act where you’re in the present so…I like that it brings me…physically…in an embodied way…to the present…I find that healing in itself…and as a ritual of taking care of yourself and other people…and there’s this line that I read recently…in Love and Rage by Lama Rod Owens that you give yourself the same care, that you would your community…you know?! And that’s the kind of thing about Seva that I feel resonates with me.. that I’m taking care of myself…and I’m also taking care of other people…in the same act.

I think that’s super healing…I don’t subscribe to these kinds of self care which are all about healing for myself as an individual, well because of my culture based on community.

I’m thinking a lot about London and how space is closing down.. not having space…physical space…to meet and now how everything’s online…and what does that mean for us?…In terms of how we grow…as a community with each other…so I think for me the gardening…also means I’m connecting to the land and community around me..and then…yeah…it’s this cycle of growth…has been an anti-dote to the art world where…it’s like constant individualised PRODUCTION, PRODUCTION, PRODUCTION. I like the process of growing food because it just teaches me a lot…about how to be in the world and how things exist and how resilient plants are but also how it is an energetic economy because I notice that the plants I give more energy to end up growing well, so it’s also this exchange and cycle of energy.

Then there’s the satisfaction of it as well…do you know what I mean?! Something tangible that you see the results of…that’s the other thing about kind of…growing and…cooking that I appreciate…

JASLEEN: A lot of us come from farming backgrounds! It’s a beautiful thing to reconnect to that in some way in the diaspora.

The leaves on the Ajwain plant are beautiful…

RAJU: I know!! I don’t want to eat them, but I realised that we need to eat them soon…so I make this pakora recipe that aunty showed me…and it’s really good…I would never have thought to do that, you just add ajwain to the regular pakora or even do it on its own if you have enough leaves. My plant is thriving!

JASLEEN: Beautiful!! ohh gosh! We’ve been chatting for like two and whatever hours!

Hi Raju,

Do you know where I can watch Dal Puri Diaspora? Been trying to find it online.

Thanks!

Hi, its only available through distributors: Distributor: http://www.vtape.org, Co-distributor: http://www.twn.org

its shame its hard to get hold of as such a great film.