Hand to Block, Pigment to Cloth, Pot to Dye.

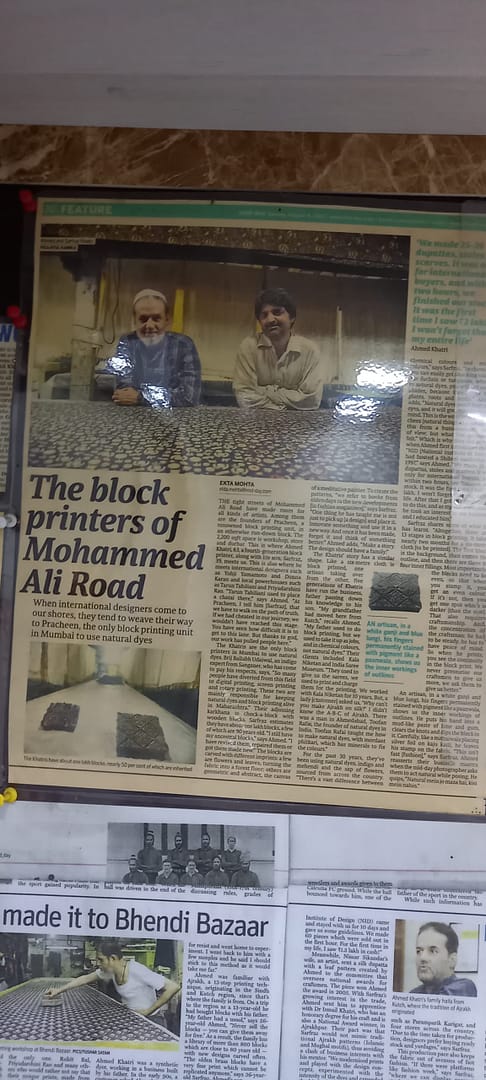

My Ajrak print workshop with Safraz at Pracheen began on a hot humid April day in Mohammed Ali Road in Mumbai. Its started with a blank canvas of organic cotton which had been prepared with ‘harda’ a fruit of the Chebulic Myrobalan tree used for its ayurvedic medicinal benefits but also to prepare cloth in mordanting before it will be dyed as it fixes the dye colour by binding to it better when overdyeing, the tannins give a warm yellow colour which can be lightened or deepened as a preference. The blank canvas stood out amongst the 10 lakh wood block behind it, suggesting an almost infinite possibility awaiting. New blocks are created all the time and yet some ancient 80-100 years old blocks are continued to be used and are either repaired or recreated new..

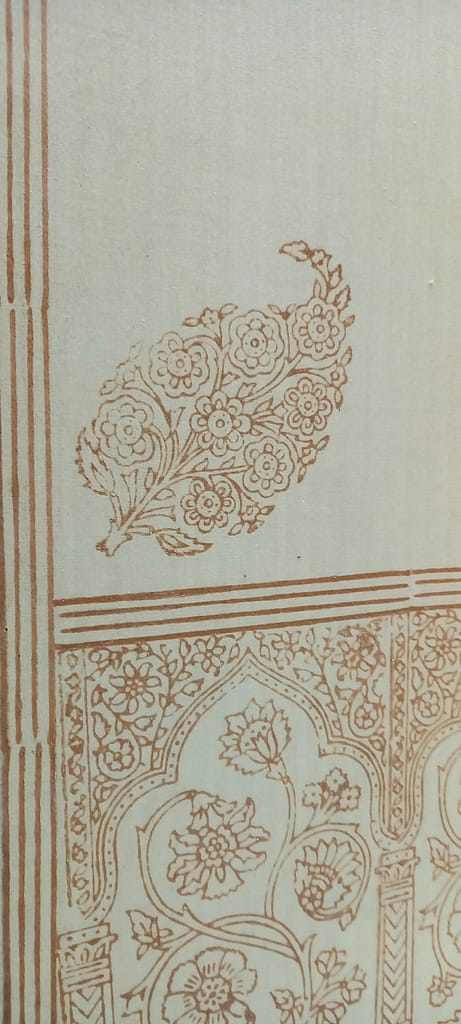

Since I am researching the migration of the aam/bi mango motif in all its manifestations (known as ‘Paisley’ in UK). I asked Safraz to share his ‘aam’ blocks with me. He had many but in the end I selected a 3 or 4 different blocks, However, each pattern contained 4 blocks each as a set: for the backgrounds, the lines and the fillings. You don’t have to use all blocks in every design, depending on what you are creating in your design, so I chose one buti design for the corners with the line and filling, minus the background, and a complete set for the borders and another complete set for a repeat pattern. This gave complete detail and layers. The process began with the resist, using lime and arabic gum, sometimes clay or mud is used. The resist is the part of the cloth that once dyed will remain in the original colour of the cloth. The next line layer was a black layer made with iron (rusted metal) and another with alizarin for the filling details. Getting the blocks to line up is very tricky. There is always a margin of error, which fortunately ends up making print look hand-made and beautiful, as you can spot the use of the hand verses a machine, the slight mishaps give the final design its unique look, ironically machines are now imitating this look by programming in visual errors!

I decided to split the cloth into two to get two designs for variation and decided for one to be more traditional and the another design to be more contemporary, organic and simplistic. I used a simple block set of two for a small aam buti motif and a leaf pattern for the border. These I scattered roughly across the cloth. These were experimental designs rather than prepared ones as I wanted to use already made blocks and designs to get an idea of the different types available. I was playful with layout and they were loosely inspired by my extensive research of textiles in various museums: Calico Ahmedabad, Living and Learning Design Centre, Kutch, Anokhi museum Jaipur and Titanwala museum in Bagru.

The cloths are then laid out in the sun for the resist to harden. This can be up to 2 days and depends on the sun and the resist. Patience is the name of the game! You must keep checking it so you know when its ready. If the resist is not hardened sufficiently then it will let the dye in. This can of course be manipulated if you want cracks or leakages as part of the design, but if you want to a clear design it is important to wait until it is ready.

While waiting for cloths to dry I observed the team at Pracheen in their daily printing. They made it look so easy, stamping away in a repetitive rhythm in teams of two. Luckily Pracheen work with small innovative collections that change often, but it was clear that there is definitely a constitution and mindset to be doing this almost everyday for so many years. Calm, precise and meditative. This is the craft for the printing caste of Hindus and Muslims, so this is literally all they do, their whole lives dedicated to it. Others in the team wash and dye the cloths and others are responsible for hanging and drying them. And of course there are the block makers who interesting enough are predominantly Muslim.

Sarfaz told me that they make the pigment for what they will use daily, first thing in the morning. They also have buckets of fermented dyes they use and feed. There are different processes involved which are important to the job such as mixing the pigment well and using muslin cloth in layers with the pigment to keep it easy and clean to use when printing. Also, weighing out the powders for dyeing in the correct ratios with the mordants. Heating them up to the correct temperature or fermenting the dyes for the right amount of time making sure to check in on them.

Dyeing and washing is also a skill. A copper pot is used to ensure stability of the dye-ing. To ensure even dyeing, the cloth must be introduced to the dye carefully, mixed around lightly and removed and gathered. Its easy for the cloth to stick to itself when wet so this step in super important. The process uses a lot of water, to make sure the dye is rinsed sufficiently, water being essential to this trade and its production, which is why it makes sense that the first printing happened in villages located near free flowing rivers in Sindh and Kutch. Access to clean water is essential.

The cloths I created used Indigo, madder and pomegranate dyes. The indigo gave a deep blue shade, the madder a deep red and the pomegranate gave the indigo a teal shade and there were subtle green touches within the pattern detail also. These colours can be manipulated and changed depending on what you want to achieve, as well as the type of cloth you use. Dupion (raw) silk carries dyes really well as it adds a sheen to it, lifting the colour and giving texture. Finally the finished cloths are washed again with a special natural soap which fixes the dye and softens the cloth. The cloths were incredibly soft and vibrant when it was finished and despite my mistakes the dyeing process was forgiving so you didn’t notice them so much. Actually they added to the hand-made touch. They also created memories of my workshop that I will not forget!